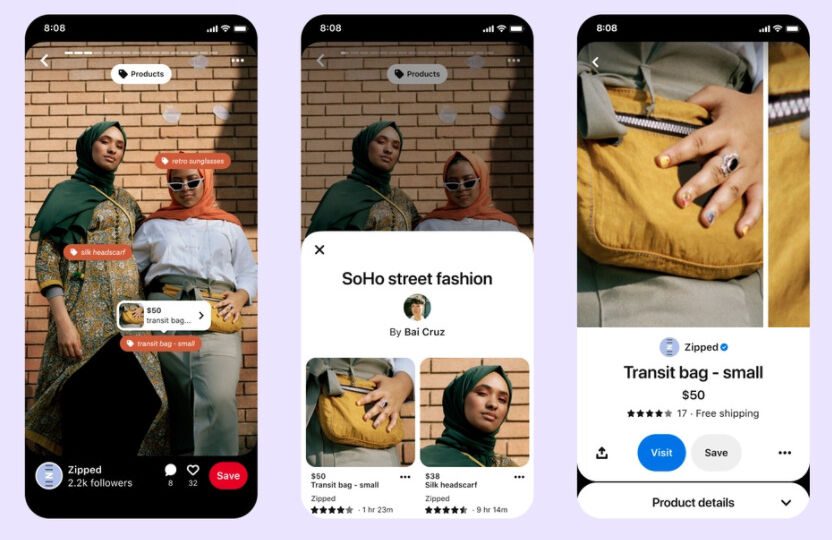

Seemingly every day there’s another announcement about a new feature enabling purchases on one social platform or another. In the last two months alone, TikTok has rolled out dedicated “Shopping Tabs” for Shopify merchants, Twitter began a pilot of its “Shop Module,” and Pinterest made it possible for creators to “control the shopability of their content” by tagging products. Suffice it to say that social commerce has arrived in America.

However, one reason for this flurry of enhancements is that there’s still considerable friction in social commerce processes. For consumers, creators and retailers alike, sifting through the ever-changing array of functionalities across platforms is still fraught with misfires, miscommunications and mistrust.

Whether social commerce will play a crucial role in retail going forward is no longer a question. It will. The questions now are twofold:

- At what point will the ability to buy products and services on social platforms become so frictionless and ubiquitous that every new feature update is no longer noteworthy? and

- What do retailers, brands and social media platforms have to do to get there?

There’s no time to waste, because consumers are already there. In 2010, adults in the U.S. spent an average of 50 minutes on mobile devices, according to eMarketer; jump to 2021, and that number has more than quadrupled, to 3 hours 46 minutes. “Think of how much time is spent on our smartphones, and the majority of that time, data shows, is on social platforms,” said Matt Maher, Founder of the technology-focused consultancy M7 Innovations in an interview with Retail TouchPoints.

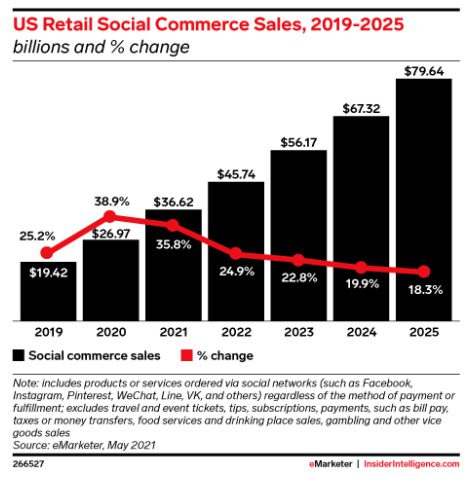

Social commerce is already a multi-billion dollar business in the U.S., earning $26.97 billion in sales in 2020. eMarketer predicts that figure will double by 2023 and reach nearly $80 billion by 2025. To catch up with consumer expectations, retailers and social media sites will need to:

- Find new ways to remove friction in the transaction processes on social platforms, most of which were built as communication networks, not shopping channels;

- Capitalize on the powerful discovery aspect of social platforms to turn passive scrollers into active shoppers; and

- Streamline systems and integrate data to build trust with wary consumers who may have had frustrating social commerce experiences in the past.

Social Platforms Aren’t ‘Shopping-First,’ but Do They Need to be?

Before the internet, shopping was (for the most part) an activity done with intent, something you set aside time for and physically sought out. Now, as we scroll social feeds, scan our inbox and check our phone notifications, we are in many ways never shopping, but also always shopping. “On digital, wherever you are, you’re essentially always just a tap or two away from buying something,” said Maher.

“When you think about being in ‘shopping mode,’ you go to Amazon, you go to Walmart, you go to Google — you’re on a path to purchase,” added Leah Logan, VP of Media Products at Inmar Intelligence in an interview with Retail TouchPoints. “Versus within social media, you see a cute outfit and think, ‘I like that jacket. Maybe I should check it out.’ Many [social] purchases are very organic. [That consumer] was not shopping, but then they decided to shop.”

That blurring of the “shopping trip” with the sundry other activities in our digital day is exactly why social media is becoming a primary vehicle for consumption not just of content, but also goods. It’s also what has made the integration of transaction functionality so complicated. Shopping is not what these platforms were built for, but that doesn’t mean they can’t adapt.

Beauty retailer Sephora has been testing the social commerce waters for several years now, and Carolyn Bojanowski, the company’s SVP and GM of Ecommerce, sees potential as retailers and social networks work in tandem to build out social commerce experiences that work for consumers. “Instagram and Facebook and others may not be experts in commerce, but I think that they are certainly learning from retailers,” she said in an interview with Retail TouchPoints. “We’ve learned from our partners in Sephora China that there’s a lot to be had here, and once the client tries something and has a good experience, we see stickiness.”

Turning Scrollers into Shoppers

The “accidental” feel of social media shopping is in fact part of its power. These platforms are forums of discovery, which is why they present such a big opportunity for brands — but also why brands must tread lightly.

“Consumers actually do more of their ideation through digital channels than physical channels,” said Jonathan Sharp, Managing Director of the Consumer and Retail Group at Alvarez & Marsal in an interview with Retail TouchPoints. “When we asked people where they get ideas and who they trust, very significantly you’ll hear, ‘friends or people I follow on social networks.’ As a brand, you can’t destroy that by intruding and saying, ‘Don’t trust your friends. Trust me,’ but if you can equip those friends with authentic use cases and stories, then that can be really powerful.”

As they walk this line, brands and retailers must have a clear vision of what exactly they hope to achieve on social channels, advised Flora Delaney, President of Delaney Consulting and author of Retail: The Second Oldest Profession. “For all brands, there are two goals — one is transactions and revenue, and the other is reinforcing my brand, building an emotional connection,” she said in an interview with Retail TouchPoints. “So you can say, ‘Let’s put out content for the Fourth of July with barbecue recipes that you can click through and buy the ingredients,’ but there will ultimately have to be a decision made about what we’re really trying to do with that content. Are we trying to sell barbecue ingredients or are we trying to establish ourselves as an outdoor entertainment expert that’s a trusted resource for our customers? This is exactly the issue with social — are you trying to remind them of why you’re a wonderful place to shop? Or are you trying to sell some stuff today? Those are two competing and different outcomes.”

Technology Matters, but What it Really Comes Down to is Trust

In addition to adapting to platforms built for content rather than commerce, simply moving outside of their owned and operated ecosystems can require a pretty big leap of faith for retailers. In some cases, their concerns are justified.

“Retailers are concerned about their brand and reputation,” said Delaney. “There are certainly a lot of posers on social media sites that look like they are a domestic brand, but we’ve all seen those pictures of the beautiful prom dress that turns out to be a really cheap, ugly thing from another country. I think retailers and consumers are really concerned about that, [and many shoppers] still feel more confident going to a dot.com.”

Add to that the fact that if a customer has a bad shopping experience on a social platform, it’s typically the retailer or brand that takes the hit, not the platform itself. “If something crashes, even though, for example, it’s Instagram’s problem, checkout was on J.Crew’s page, so my negative sentiment is going to be with J.Crew unless it’s blatantly obvious that Instagram failed,” Said Maher.

“The way we’ve approached it is, [the social transaction] should be as seamless as if you’re checking out on Sephora.com,” said Bojanowski. “Certainly there are some beta moments, but that has been our North Star. You’re checking out at Sephora. I don’t care if you discovered it on Instagram and you’re still on the Instagram app, if there is a client complaint or return they’re coming back to Sephora, so regardless, it should feel as good as our website.”

In many ways consumers’ expectations for social commerce experiences are ahead of what platforms and retailers are currently able to provide, which can be frustrating for all parties. Take for example a customer who puts an item in a cart on a retailer’s page within Facebook, steps away, but then expects the item to be in their cart when they later go to the retailer’s dot.com to checkout. Creating that kind of linkage across owned platforms and third-party ones is technologically very complicated, but consumers increasingly expect such seamless brand experiences as a matter of course.

In fact, the insularity of social media sites is another sticking point to wider adoption of social commerce by retailers, and a large part of why transaction experiences can become so clunky.

“If you’re going to sell on those platforms, you pay a tax, and that tax is data; you’re not going to have all your first-party data,” explained Maher. To avoid this (as well the rev share many platforms impose on native commerce functionality), many brands run ads that lead back to their own platforms, but that creates a jagged, often unsatisfying consumer journey. For example, the break in communication between social media ad and retailer website is often what causes things like stockouts of products being advertised and other sales snafus.

“We call Facebook and Instagram walled gardens, because that’s how they function,” added Logan. “They want to make sure that if you want reporting or if you want to target, it’s only within their four walls. Retailers are very similar — they also want to make sure they have their own data, their own sales attribution. Eventually those two parties are going to have to come together and knock down some walls for the overall benefit of the consumer.”

Right now the social commerce ecosystem in America is messy, but we’re already moving toward a day when social commerce will become another pillar of the shopping journey alongside websites and stores. “We will get to a point where anything I see in my social entertainment universe, I can tap away to purchase; that is an inevitable future,” said Maher. “But [social commerce] is an evolving organism. As with most things we will probably overestimate the effect in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.”