Although we’re taught that it’s not polite to talk about money, many people can’t resist crowing about what a great bargain they got by buying via resale. (Some are just as eager to tell you how much they sold a used item for.) But for those companies in the business of resale, money can be a touchy subject. That’s because, despite resale’s increasing popularity with consumers, these firms are finding it incredibly difficult to generate profits.

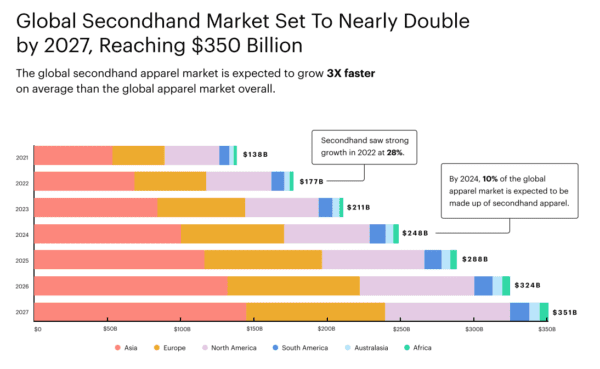

These money woes are not because consumers aren’t spending — ThredUp’s latest annual report predicts that secondhand sales will double by 2027 to reach $350 billion globally — but because online purveyors of secondhand products face a number of unique challenges.

With the ecommerce boom days of the pandemic now behind us, the heat is on — public companies operating in resale, like ThredUp and The RealReal, are finding themselves under increasing pressure from investors and shareholders to not just make headlines but actual profits. At the same time, traditional retailers are entering resale in droves, oftentimes in partnership with platforms like ThredUp or solutions like Trove and Archive. In addition to the competition of a more crowded field, these retailers are likely to face the same profitability pressures as their tech forebears. And while companies can “earn” a nice bump in brand image, if resale programs don’t make sense financially it’s doubtful they will work in the long term.

“[Resale] is a double-edged sword,” said Andy Ruben, Founder and Executive Chairman of recommerce solution Trove in a recent Retail TouchPoints podcast. “It’s a channel that has to be built out on its own and integrated with other channels. Is this a one-time story that you’re going to get a headline for because you’re going to sell 35 items? Or is this something that you’re able to build by keeping customers close to you? Is it happening at good profit margins? And are you able to scale the platform to millions of items, [to a point] where this can become a meaningful percentage of your business? Brands need to navigate the business model underlying how they’re doing resale and ultimately, they should make sure that they are building a growth channel; [otherwise] it’s just a marketing program called sustainable.”

Easier said than done, so we’re taking a deep dive into the challenges of turning resale into a revenue-generating channel and how some platforms are tackling them in this two-part series. [Read Part 2, focused on the tactics brands are taking to make resale financially viable, here.]

Challenge #1: SKUs of One

“There are a number of barriers to profitability for anybody in this space, and the first is efficiently acquiring quality supply,” explained Matt Kaness, CEO of the new resale marketplace GoodwillFinds.com in an interview with Retail TouchPoints. “Whichever marketplace you’re talking about, if you don’t have sellers who have a continuous supply of products that consumers want, you don’t have a marketplace.”

Even with reliable supply sources, the reality is that you’ll be dealing primarily with items that are one-of-a-kind “snowflakes,” as CarMax’s EVP of Strategy and Product Jim Lyski described them.

“Most formal retailers are built around a parent or child SKU, and then you have maybe 100,000 units — every unit looks the same and you can process every unit in the same way,” said Ruben. “Whereas when you’re buying items back from customers, you’ve got to understand what the condition of that unique item is, because you might hand a customer [for example] a larger gift card or a smaller gift card depending on the item. Either way, you could either lose money with too large of a gift card, or you could end up missing the best options because you’re not giving enough money.”

While Trove’s partners typically offer payouts in the form of branded gift cards, the same dynamics around accurately grading and pricing items hold true for managed marketplaces like ThredUp or The RealReal.

Challenge #2: Receiving and Processing

When it comes to handling the supply of secondhand goods, platforms currently use one of two models: peer-to-peer or managed marketplace. Peer-to-peer platforms like eBay, Poshmark or Depop essentially push the logistics onto the individual sellers, who create listings, set pricing and handle fulfillment themselves. No physical infrastructure is required beyond the platforms’ technology, which offsets a lot of costs.

Managed marketplaces like ThredUp, Rebag and The RealReal enable a much more consistent, streamlined consumer experience by buying products from sellers and managing everything from listing to fulfillment themselves. Of course, that requires much more physical infrastructure, which as Kaness pointed out is “hard to scale profitably until you get to a certain critical mass.”

The scalability factor is also very different across these two models, according to Ruben: “Peer-to-peer has been a real innovation that’s allowed a lot more brands to launch, but the experience for brands and customers is very different. The brands have a lot less control of their brand, and there’s a lot less [scalability] in the model. What we have always favored, and what the brands that we support do, is owning these items just like they own first-sale items. We believe that for [resale] to really scale, it’s got to be as easy as it is to walk in and buy [anything else] you want. And when you’re no longer using an item, it’s got to be just as easy to hand it back and get value back out of it.”

Scaling customer uptake is one thing, but scaling a profitable business out of it is another beast altogether. ThredUp, which runs one of the country’s largest managed resale marketplaces, has invested millions in building and automating the facilities and technologies required to do this at scale. But profitability, or even just reaching break-even, has remained elusive, prompting a “meaty experiment” (as CEO James Reinhart put it) in pulling new levers to optimize the unit economics.

“When you’re processing hundreds of millions of SKUs a year, there’s a reasonable amount of complexity in understanding what are the right items and how to shape your marketplace to be efficient,” said Anthony Marino, President of ThredUp in an interview with Retail TouchPoints. “We’ve used the past several quarters as an opportunity to really hit that hard and get it right, and we’re seeing a really promising response from our seller community and from our buyers.”

More on exactly how ThredUp is doing that in Part 2 of this series, but first, there is one other often overlooked expense for managed marketplaces…

Challenge #3: What to do with the Stuff you Don’t Sell

Ken Goldstein is the Chairman and CEO of ThriftBooks, a managed marketplace that focuses solely on selling books and other media. “We’ve had conversations about going into other categories, and when we do the test metrics, they don’t look as good,” he said in an interview with Retail TouchPoints. “One of the reasons is that right now everything we have is recyclable — it’s 100% clean, dry paper, and that will always bring us some remainder value. Whereas if you look at apparel, not all of that is sellable or recyclable, so then at the end of the day you have a disposal cost.

“I don’t have disposal costs because everything we do can be turned back into something useful, but if I wound up with a whole bunch of chemically coated materials or acrylics or other things, I would legally have to pay a disposal cost for that,” Goldstein added. “You have to build that into the business model.”

But…Resale Isn’t Just About Money

Creating a profitable resale business model is vital, but not all benefits can be measured in dollars. Resellers’ ability to burnish their sustainability profiles can help them attract and retain the growing contingent of bargain-seeking and eco-conscious customers.

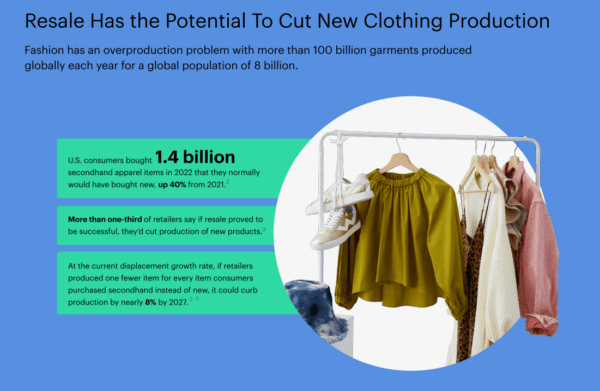

And there’s no doubt that customers, especially younger ones, are demanding more sustainable options. U.S. consumers bought 1.4 billion secondhand apparel items in 2022, according to the ThredUp report, an increase of 40% from 2021. Perhaps more important is that the percentage of consumers who said those used items replaced products they would have purchased new is also up 40% year over year. “The consumer is making the connection in their mind that there’s a smarter, more sustainable way to consume,” said Marino. “It’s better for the environment and better for my wallet, and I’m going to seek it out and do it.”

“This is the single most important retrofit on a sustainability topic anywhere in retail, bar none,” said Ruben. “For any brand that really cares about sustainability, you have to have a strategy to get more money out of the things you make. And what I’m most excited about is the platforms that are supporting the brands that have the opportunity to really change the way we shop. When Patagonia themselves sells a Nano Puff [jacket] for the fifth time to a fifth child, that is three to four jackets that are never made. That is a brand that is gaining customers, gaining market share, gaining loyalty and making money from existing items, not from new production.”

[Want more? Check out Part 2 of this series, where we take a look at how companies like ThredUp, Thriftbooks and GoodwillFinds.com are working to make their resale initiatives financially viable.]