As it has for several years, Black History Month 2022 boasted a sizeable assortment of retailer programs designed to spotlight products made by Black- and BIPOC-owned companies. And this year saw a welcome focus on not just identifying these brands but also creating the tools and infrastructure that would allow them to scale: the nuts and bolts of sourcing, distribution, financing and placement on store shelves and ecommerce websites.

“Black designers and business owners need distribution pipelines that are not just about curating for a trend or a moment,” said Roslyn Karamoko, Founder and CEO of Détroit is the New Black (DITNB) and VP of Strategic Business Development for Neighborhood Goods in an interview with Retail TouchPoints. She noted that the new and urgent question for Black business owners (and for the retail industry at large) is, “How do you want to scale? How do you get the product to the customer in a really streamlined way that allows emerging businesses to remain profitable and sustainable from a business standpoint?”

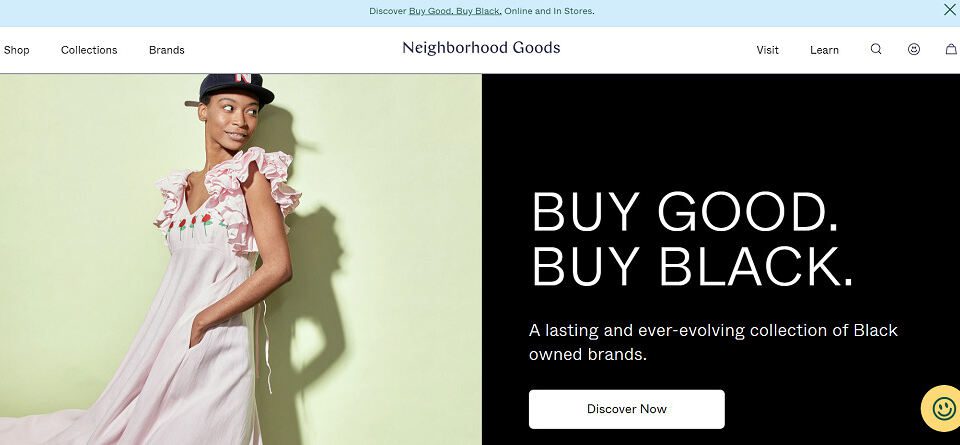

Karamoko, who joined Neighborhood Goods in August 2021, curated the retailer’s “Buy Good. Buy Black” initiative, which provides a platform for unrepresented Black-owned brands. The Neighborhood Goods business model includes showcasing emerging digitally native brands via a constantly rotating product experience, both online and in its three brick-and-mortar locations (in Plano and Austin, Texas and NYC’s Chelsea Market).

This model is a good one for Black-owned brands to “meet customers where they are and grow organically,” said Karamoko. While the growth of online commerce and social media has made it easy for direct-to-consumer (DTC) businesses to start up and ship items to customers, moving such a business to the next level can be a lot tougher. Unfortunately, the business requirements of many retailers make the hurdles even higher.

“Getting into new demographics and new geographic locations, Black brands want to partner with the larger department stores, but their models can be very challenging for smaller brands,” said Karamoko. “There are issues around compliance, EDI and margin agreements that may or may not be advantageous to small brands, which are not always profitable if they haven’t yet scaled up.”

Working with retailers like Neighborhood Goods, in contrast, allows these brands to “meet shoppers where they are and grow organically,” said Karamoko. “They can enter new markets and understand new analytics to potentially change course, if needed. It’s a feasible way to start in physical retail without taking on the overhead and lift [that’s required] independently.”

Rise of the ‘Inclusive Consumer’

There are strong indications that many consumers are ready for these changes. An October 2021 survey by McKinsey revealed that two out of three Americans said their social values now shape their shopping choices, and that 45%, representing more than 100 million shoppers, believe retailers should “actively support Black-owned businesses and brands.”

McKinsey identified members of this group as “inclusive consumers,” and noted that their desire to purchase Black-owned brands is often frustrated by the products’ underrepresentation on store shelves, cited by one in five inclusive consumers. Some retailers have created in-store departments or online portals to lead shoppers to Black-owned brands, including the Buy Black Storefront of ecommerce giant Amazon.

All these challenges play out in retail as a whole: while approximately 14% of the U.S. population identifies as Black, Black-owned brands generated only about $83 billion in 2020 sales — less than 1.5% of the $5.4 trillion of total retail spending, according to McKinsey.

Creating an Infrastructure for BIPOC Retail Success

The most visible action that many retailers have taken has been participation in the Fifteen Percent Pledge, a promise to devote at least 15% of shelf space to Black-owned brands. The 28-plus participating companies include some of the biggest names in retail, including Nordstrom, Sephora, Macy’s and its brands Bloomingdale’s and Bluemercury, Ulta Beauty, Rent the Runway, Hudson’s Bay, Crate & Barrel, West Elm, J.Crew, Gap and Gap Inc. brands Banana Republic, Athleta and Old Navy, and the Indigo bookseller chain. The organization claims on its website that it has shifted almost $10 billion in revenue to Black-owned businesses since it started in May 2020.

Best Buy, which has committed to spending at least $1.2 billion with BIPOC businesses by 2025, is pushing the limits of its diversity activities into the supply chain. The retailer is working with RangeMe to help it discover and work with a more diverse range of suppliers, as is Walgreens.

Other retailers are developing ways to mine the talent of their own BIPOC employees, such as Abercrombie & Fitch with its “For Justice” collection. The retailer has long been criticized for a lack of diversity in its hiring and advertising, as well as a lack of inclusiveness in its product selection and sizes, as noted in this Washington Post article from November 2021.

The For Justice products are designed by members of the retailer’s BIPOC Associate Resource Group, and designs feature the associates’ own words calling for unity, equity, the need to elevate Black voices and respect for both Black History and Black futures. Additionally, Abercrombie is donating $250,000 in anticipated proceeds from For Justice sales to The Steve Fund, an organization supporting the mental health and emotional well-being of young people of color.

Exploring the Diversity Within the ‘Black Diaspora’

For Karamoko, these efforts are positive but represent just the beginning of what needs to be done. “It’s a no-brainer that we should support underrepresented brands, but this can easily go into a ‘charity’ space,” she said. Retailers and brands also should be asking “how you create a curation that connects with people and explores black culture and educates people. A product is an expression of a person or culture in the same way that art is, so [we need to ask] how the brands that are selected are representative of the Black Diaspora.”

Karamoko cited Liha Beauty, which sells products that mix the founder’s own heritage — a West African father and a British mother — to create a mixture of “natural African roots and a quintessentially British attitude,” according to its website. “They’ve taken formulas and materials and mixed oils and butters that can replace 15 of your beauty products with one,” said Karamoko. “That fusion of Afro-British reflects how Blackness travels through Haiti, London and America.”

Another example of the personal and familial being translated into retail is Fanm Mon, which offers apparel based on the founder’s Haitian and Turkish heritages. “It’s a lot of linen fabric and embroidery, and it’s an expression of a component of Black culture,” said Karamoko. “Black people all over the world are living varied experiences, and that’s what it means to ‘Buy Black.’ The question that needs to be answered is, What is Black, and what does it look like in product form and retail form?”