For more than 150 years, Parisian department store La Samaritaine has overlooked the banks of the Seine, a sweeping expanse of glass and intricately painted iron that proudly proclaimed the store’s position at the center of French commerce, both geographically and ideologically.

Until 2005 that is, when the doors of La Samaritaine were summarily shuttered. The century-old building was in need of urgent repairs to address safety issues posed by such ailments as out-of-code wooden flooring and aging electrical systems. A lack of profitability also had plagued the establishment for decades, although that was not what officially prompted the closure.

Employees staged a sit-in, fearing the beloved, if a bit bedraggled, “La Samar” would never be reopened. Their fears were not entirely unfounded. Repairs were initially projected to last two years, and yet for 16 years she sat, dust gathering on her famed glass roof, as she awaited her fate.

Those 16 years weren’t exactly kind to her counterparts: Debenhams entered administration for a second time and was brought it back as an online retailer by new owner Boohoo Group; America’s oldest department store, Lord & Taylor, met a similar fate; the bankrupt Barneys was boiled down to intellectual property; Selfridges’ owners launched an auction to sell off the chain; and Harrods resorted to selling discounted stock in a mall.

But this June, things turned out differently for La Samaritaine. After a decade and a half of bureaucratic squabbles, legal setbacks and €750 million ($871.4 million USD) in renovations, punctuated by a global pandemic, this “grand magasin” has finally, triumphantly reopened its doors under the stewardship of its latest owner, luxury fashion house LVMH. It was a moment that even LVMH executives had begun to fear might never happen.

This is more than just a story about one department store’s close brush with death. It’s a story about the reimagining of the department store as an entity, and a historic investment in the belief that shopping is above all an experience, one that cannot ever be fully replicated in the digital world.

With the revival of La Samaritaine, LVMH offers a fresh vision for the future of in-person retail. The result is:

- An artful combination of historic elements restored to their former glory and contemporary design, both in the architecture and merchandising;

- A mixed-use space in the most extreme sense of the term, including both a luxury hotel and socialized housing; and

- At its heart a luxury destination, the store has entry points for visitors of all means including cafés, a gift shop and free experiential components such as an art gallery.

[For a full gallery of photos, scroll to the bottom of this article.]

No One Said Reincarnation Would be Easy

So what took so long? Sixteen years is an inordinate amount of time to leave so much real estate in the most expensive neighborhood of Paris vacant. The short answer is that LVMH’s plan to reincarnate the iconic but failing department store as a luxury destination met with a bit of resistance (this is France, after all).

When LVMH first took a majority stake in the store in 2001, it planned to keep the store open while undertaking upgrades and a redesign. Those plans were thwarted, however, when the store was forced to close for safety reasons in 2005.

At the time, LVMH was fresh off its acquisition of another historic retail institution, Le Bon Marché, the oldest department store in Paris, so the company took the mandated closure as an opportunity to completely reimagine the store. LVMH laid out a bold mixed-use plan that would turn La Samaritaine into a luxury destination complete with a high-end hotel. That vision, however, was not popular with the store’s other major stakeholder — the Cognacq-Jay Foundation, a charitable fund created by La Samaritaine’s founding couple, which owned a 40.6% stake and wanted a plan more in line with “their founders’ mission.”

Eventually the Foundation huffed away from the negotiating table but not without, in typical French fashion, having the last word: “We are letting the majority shareholder [LVMH] take sole responsibility for its decisions, which have in any case always been made despite our opposition.”

In 2010, LVMH bought out the Cognacq-Jay Foundation to become the sole owner of La Samaritaine, and it seemed the company’s plan for the historic site would move forward. But in 2012, preservationists and heritage groups requested the cancellation of LVMH’s permits. The case made its way in and out of French courts, and all the while La Samaritaine sat, waiting. In 2016 the dispute reached France’s supreme administrative court and LVMH emerged victorious, with the Conseil determining that the lower courts had been too strict in their interpretation of city planning regulations. LVMH’s ambitious plan could finally proceed.

A Study in Contrasts

Six years of renovation and construction ensued, spearheaded by LVMH subsidiary, duty-free retailer DFS. COVID-19 caused additional delays, but the new Samaritaine Paris Pont-Neuf finally reopened its doors on June 23, 2021. The result is a study in dichotomy — rich and poor, old and new, unattainable and accessible sit alongside and atop one another in this nostalgic yet contemporary complex.

“DFS designed Samaritaine’s rebirth, firmly anchored in its roots, but with an eye resolutely turned toward the 21st century,” said Eléonore de Boysson, President of Europe and the Middle East at DFS Group in a statement. “More than just a place to shop, we want Samaritaine to be a place of discovery, surprise and experience.”

In its heyday, La Samaritaine beckoned visitors with the tagline, “On trouve tout à La Samaritaine” (“One finds everything at the Samaritaine”), but that is no longer the case. The 20,000 square meters (215,000 square feet) reserved for retail in this sprawling complex are primarily high-end — Hermès bags greet visitors at the main entrance, and the historic grand staircase is freshly adorned in gold leaf. (Not surprisingly, LVMH brands feature prominently.) The façade facing the river is now a five-star hotel, Cheval Blanc, where a deluxe room with “marble curves” and a footprint the size of the original Samaritaine store is the cheapest option. Rooms start at €1,500 (approximately $1,745) per night.

And yet on the other side of the building are 96 socialized housing units, a day care center and 20,000 square meters of office space. LVMH conceived of and shepherded this plan, but these more public-minded elements also were driven by legislation requiring that Parisian municipalities set aside 25% of their habitable living space for socialized housing by 2025.

The result is an extreme version of “mixed use” that would almost certainly never even be considered in the U.S., but America has the space to afford that kind of dissociation. Paris is a crowded city, and becoming more so, with a progressive mayor, Anne Hidalgo, who was a vocal proponent of LVMH’s plan for the site, saying “We need to know how to bring modernity to this city, and modernity is not the enemy of heritage.”

Paris’s first arrondissement, where La Samaritaine is situated, is the city’s most expensive neighborhood. The average rent is €2,310 (nearly $2,700) for a 75-square-meter (800-square-foot) apartment. Renters like those living in the building at Samaritaine pay €375 to €600 for the same space.

“Providing social housing here is justified,” read a statement from the general management of La Samaritaine about the mandate. “It is the symbol that La Samaritaine belongs to all Parisians.” It is, however, a strange symbiosis to witness. The balconies of these low-income apartments, reserved for citizens in the “most precarious” circumstances, look down through a glass ceiling at cases of jewelry and racks of clothes that the inhabitants above could most likely never afford.

Restored and Reimagined

In addition to the hotel, housing, day care, offices and retail space, the finished Samaritaine project also includes:

- 12 restaurants;

- A deluxe spa;

- A beauty salon;

- An art gallery;

- The Boutique de Loulou, a street-level gift shop named after one of the founders of La Samaritaine and dedicated to locally made, exclusive products, including Samaritaine souvenirs;

- The Factory, where guest artists create on-site works;

- The largest beauty hall in Europe. (Technically, the beauty department at Harrods is larger than this site’s 3,200 square meters, but Brexit has excluded the UK from European rankings);

- A lounge area that can be rented for private events; and

- Five private shopping “apartments” that can be rented for sessions with personal stylists, or by those who simply want a place to escape the crowds.

If it sounds like a lot, that’s because it is, but these many disparate elements are artfully melded together through intricately detailed architectural and interior design.

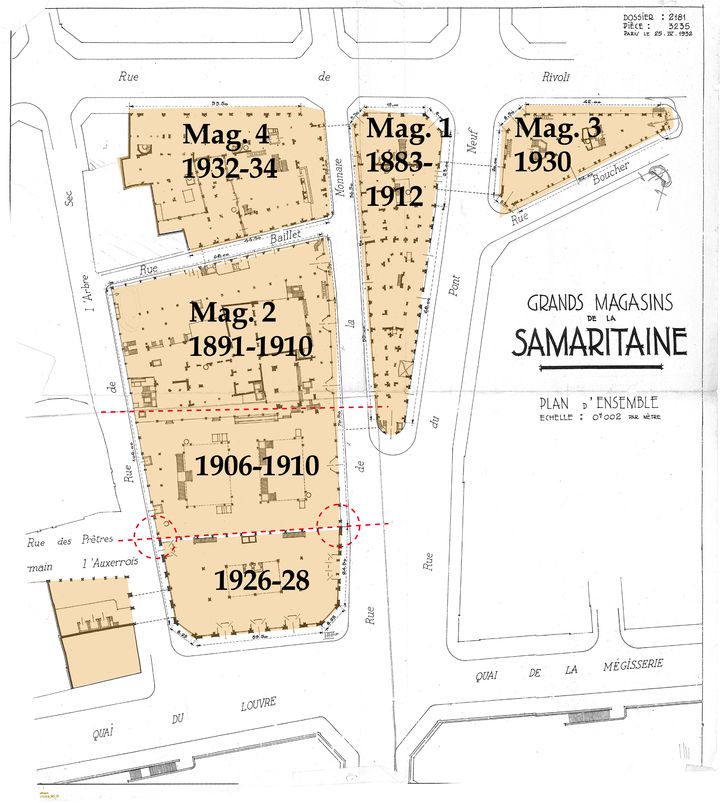

When La Samaritaine first opened in 1870 it measured 48 square meters (516 square feet). The La Samaritaine we know today stretches across a complex of four neighboring buildings that total 70,000 square meters (more than 750,500 square feet).

What has reopened is “Magasin 2,” the largest of those structures. The building’s famed Art Nouveau and Art Deco elements have been painstakingly restored, most notably the glass roof erected in 1907, which was returned to its original shape and colors. The only modern concession was electrochromatic glass that tints in response to brightness.

The façade on the opposite Rue de Rivoli side of the building was reimagined in a contemporary context by Japanese design firm Sanaa. Featuring an irregular wave pattern, this new face of La Samaritaine is meant to “embody the modernity, fluidity and poetry” of the store’s “rebirth.” Fittingly, the more traditional luxury retail elements are located on the historic Seine side of the building, with the more modern Rue de Rivoli side featuring “a concept store” of contemporary offerings. “The glass building on Rue de Rivoli is a playground of fashion inviting the visitor to discover the latest trends in urban fashion while enjoying an espresso sipped in front of street art,” according to marketing materials.

All told, the project cost LVMH $895 million (not counting the hundreds of millions spent buying the store in the first place). Only time will tell if that investment will pay off, but it almost certainly depends on whether this new version of La Samaritaine can earn the esteem of Parisians the way its previous incarnation did, while simultaneously becoming a destination for moneyed foreigners.

“In this ever-changing place, there is always something happening to catch the eye of Parisians strolling by as well as discerning tourists in search of ‘art de vivre,’” said Boysson hopefully in a statement at the reopening. As to the latter half of the equation, the store is apparently featured prominently in season two of the hit Netflix show Emily in Paris, so that should help.

Hover over a photo in the gallery below to read more details in the captions, or click on a photo to expand and open the full-size images.