Ever since I was a little girl, I have been a fan and follower of fashion. Why? Because I think it’s an effective way for people to convey their personality without saying a word. By wearing a specific color, silhouette or style, I can reveal what I’m thinking and feeling in that moment.

Ever since I was a little girl, I have been a fan and follower of fashion. Why? Because I think it’s an effective way for people to convey their personality without saying a word. By wearing a specific color, silhouette or style, I can reveal what I’m thinking and feeling in that moment.

But over the past few years, there has been a significant shift in how a lot of consumers see fashion. Instead of being a representation of themselves and their lifestyles, it’s merely a way for them to keep pace with the latest runway and celebrity trends. Hence the growth of fast fashion retailers such as Forever 21, H&M and Zara.

In my interview with Amanda Bopp, Director of Client Leadership at dunnhumby, she noted that fast fashion, as a category, is designed to keep pace with customers’ on-demand lifestyles. “It provides the customer with immediate access to trends at accessible price points,” she said. “Further, the ‘fast’ nature of fast fashion drives customer interest, as product turns quickly, there is always something new to discover, driving incentive for repeat visits.”

Fast fashion retailers have thrived as a result of consumers’ insatiable appetite for apparel and accessories that look high quality, but have a low price tag.

“Customers seek the design aesthetic of higher-end products, but are not always willing to make the investment, particularly in a fashion item which loses relevance quickly,” Bopp said. “They want the right looks, but are cautious when it comes to spend. H&M’s capsule collections with designers such as Isabelle Marant and Lanvin provide customers with access to world-class designers at accessible price points.”

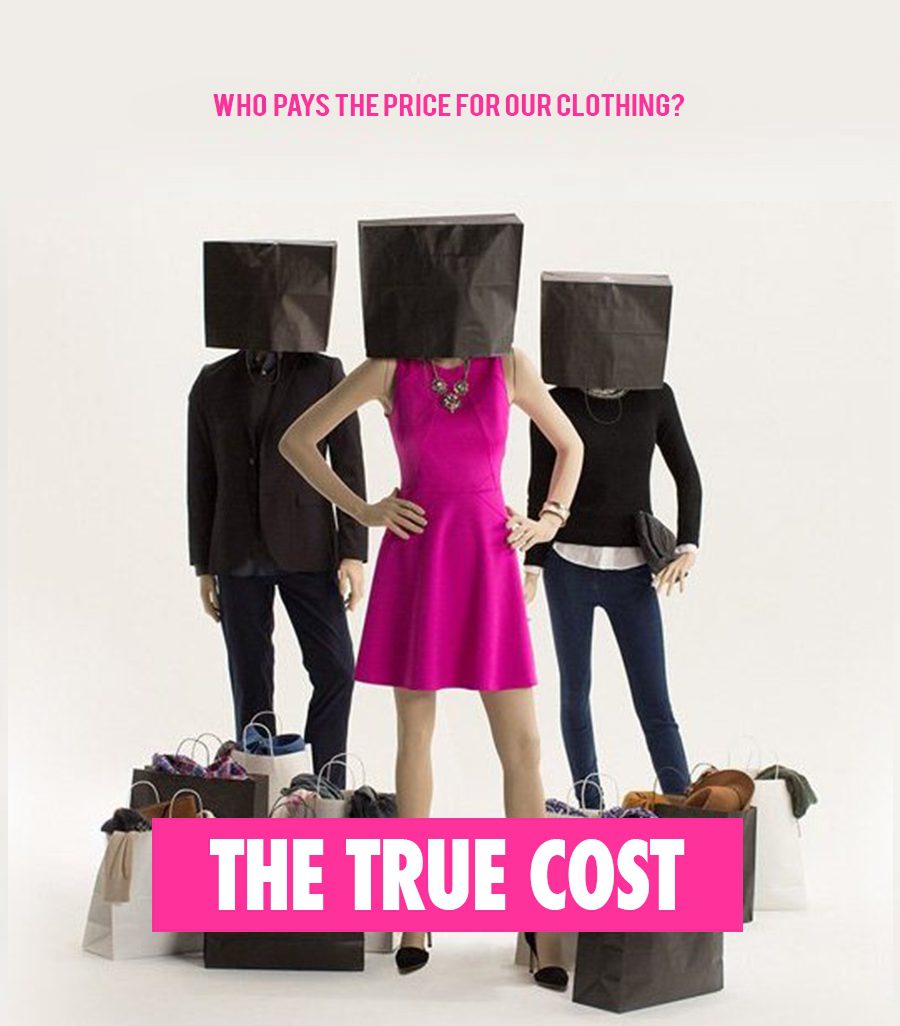

Over the years, I’ve reported on (and purchased from) many of these capsule collections. I find it refreshing that seemingly untouchable brands are trying to connect with all walks of life. However, I recently came across a documentary on Netflix, called The True Cost, which has encouraged me to rethink the impact of fast fashion not only on the environment but also our fellow man.

The True Cost reaffirms Bopp’s above points: Fast fashion retailers turn new product lines constantly throughout the year. So instead of having two or four collections based on core seasons, these retailers can cycle out up to 52 collections — one every week. But as I was watching the film I couldn’t help but question whether consumers have naturally demanded this endless cycle of product, or if fast fashion retailers have nurtured us into wanting it.

After all, as a consumer, I recognize that although the price points of these products are very low, the quality also can be rather low. I’m not alone in that realization, according to Bopp.

“I think the reason why fast fashion retailers are still making an impact despite quality issues is because of the current mentality of consumers,” Bopp said. “In the past, shoppers savored items that they purchased and had the mindset to take care of products. However, in recent times, there’s been a great attitudinal shift among consumers. Shoppers these days are less likely to keep items for a long period of time and would rather cycle through multiple new items.”

These shifts in consumer perceptions, and the rapid rise of fast fashion retailers, have created a dizzying impact on the entire world. The most significant, one may argue, is the overall treatment of workers who are crafting the items for sale. In order to keep product prices low, retailers need to outsource the making of goods to low-cost economies where the wages also are low.

Although interview subjects in The True Cost argued that working in a sweatshop was better than other employment options in their home countries, these employees are plagued by low wages and poor working conditions. Some have even fallen victim to disasters, such as the 2013 building collapse in Bangladesh, which claimed more than 900 lives.

The Customer Is In Control

Of course, as consumers, we are fed advertisements that say “get more stuff” and “the more stuff you have, the happier you’ll be.” That is why we end up buying $10 dresses only to wear them once and throw them out. In fact, the average American discards up to 82 pounds of textile waste each year, most of which is not biodegradable, according to the documentary.

But at the end of the day, consumers are the ones who are in control.

“The customers are in charge,” designer Stella McCartney explained in the documentary. As a result, consumers “don’t have to buy into” how things are done now. She added that now, her excitement lies in questioning and challenging current operations, and that it’s something the entire fashion industry needs to do.

Patagonia’s VP of Environmental Affairs, Rick Ridgeway, added that as a company, Patagonia is encouraging its consumers to understand the impact of extensive consumption. “We ask them to join us in questioning consumption behaviors,” he said. “We can’t address the problems and decline in the health of the planet unless they do.”

The reality is we are in an industry fueled by supply and demand. Consumers are craving fashionable yet affordable products and retailers are only trying to keep pace and give shoppers what they want. However, Bopp noted that there are ways brands and retailers can differentiate themselves from the competition without resorting to slashing prices and accelerating product cycles.

“Transparency, a trend marked by increased customer interest in how goods are made, is a value retailers can leverage to compete effectively,” Bopp said. “If retailers can tell stories around product quality and craftsmanship, they can differentiate their goods relative to product sold in fast fashion outlets. This not only highlights a value proposition, but also allows customers to feel good about making perceived responsible choices.”

It will be interesting to see how brands and retailers attempt to educate consumers about how products are made. I’m also eager to learn about how merchants refine and expand their sustainability efforts on a national and global scale.