Online grocery is a market that’s flooded with both traditional grocers and young startups, but all share a common challenge: figuring out how to control delivery costs, delivery times and (perhaps most important to the consumer) freshness of food.

Online grocery is a market that’s flooded with both traditional grocers and young startups, but all share a common challenge: figuring out how to control delivery costs, delivery times and (perhaps most important to the consumer) freshness of food.

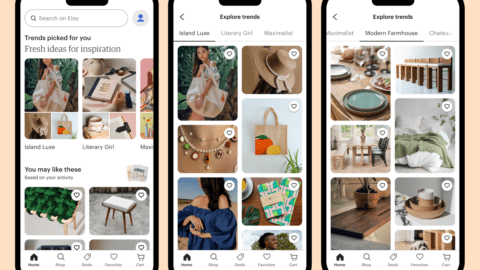

Founded in 2016, San Francisco-based Farmstead sought to solve these problems by accurately predicting supply and demand of locally-sourced goods. Leveraging proprietary machine learning, inventory and logistics platforms, Farmstead guarantees delivery within 60 minutes throughout the San Francisco Bay Area. Shoppers pay a $4.99 fee for one-hour delivery, and $3.99 for three-hour delivery.

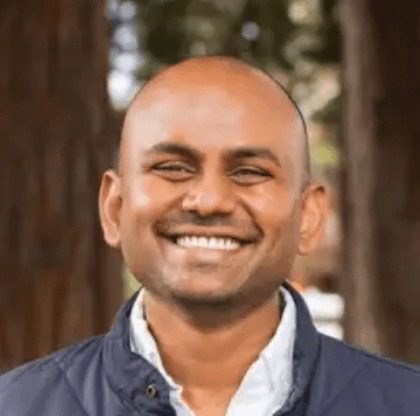

In an interview with Retail TouchPoints, Pradeep Elankumaran, CEO and Co-Founder of Farmstead, described the online retailer as a “technology company, first and foremost.” Elankumaran discussed how Farmstead:

- Shrunk its food waste percentage to under 10%, well under the supermarket average of 35%;

- Built its own merchandising, inventory control, picking and packing and route generating software;

- Plans to leverage machine learning and AI to predict factors such as how many drivers are needed on the road and how many employees are needed to pick and pack products; and

- Uses online search to determine future products.

RTP: From a value standpoint, what was online grocery missing that led you to start Farmstead?

Pradeep Elankumaran: When this started in 2016, the only major delivery option in my neighborhood was Instacart. There was Amazon Fresh as well, but it was pretty dire and the selection was weak. It didn’t have the right products and the packaging was horrific.

I had a two-year-old who all of a sudden was drinking a lot of milk, and I had another child on the way. Picture going to the supermarket three or four times a week at around 7:30 to 8:00 pm, to Safeway or Whole Foods, buying the same things over and over and dealing with big lines. It’s a very stressful situation, and I was complaining to my now co-founder, ‘You’re having a baby on the way as well, do you have any ideas of what we can do here?’

Over time, he suggested posting on the Nextdoor community for Mountain View, Calif., asking if anyone was interested in weekly delivery of staples such as milk, eggs, yogurt and bread. We figured if 10 people responded, then we could get someone to do shopping for us as a private shopper. In two days, 200 people said ‘yes’. We weren’t really looking for that, but when that kind of interest is shown, it’s really hard to say ‘no’ there.

As engineers, we dug further into the space and realized there’s a much more interesting product here. If we put the right software in the right places and leveraged new delivery models that are currently coming into play, it would be possible for us to deliver groceries to you perfectly every time — without any substitutions, delivered in a very flexible window of time, while at the same time you don’t pay any more than you’d normally pay in the supermarket.

We took a deep dive into how this was possible — we have to take perishable supplies that we buy wholesale and connect it to demand using digital channels. Can we can get milk in our warehouse and sell it to people using online channels, doing online marketing before the milk expires? Can we write enough software to orchestrate all of this so that we can rapidly scale these locations that we were building?

The key is that Farmstead isn’t a retail store, we are a smaller-format warehouse. Our locations are 3,000 and 5,000 square feet, and we don’t carry every single item at the supermarket, we carry about 1,000 SKUs and invest in many categories. When we add more items, we’re actually adding more categories. If we want potato chips, we’ll have three SKUs of potato chips, not 50.

The items that we pick are usually very high quality, but our mission is to make the high-quality foods accessible to everyone. Because of that, we try to pick multiple price points in these categories as well and get the best possible quality. We sell both commercial and organic produce, cheap ketchup and fancy ketchup. We don’t really want you to position between “lower quality” or “this is more expensive so it’s higher quality.” Whatever you’re able to afford you should be able to buy on Farmstead.

RTP: Weekly subscribers have an hour before their delivery window starts to adjust their order. How does Farmstead execute such quick turnarounds based on these adjustments?

Elankumaran: That level of flexibility is very difficult to pull off, and we had to write a lot of software to support the operational efficiencies that are required to deliver rapidly. The software is really the heart of Farmstead. We have software to manage inventory, reduce food waste, schedule a labor pool to pick and pack these orders in a very efficient way, and recruit and retain drivers.

One of the key concepts here is that this is a rare instance of a technology company spending this much time and attention on the mechanics of perishable products. We first didn’t want to write all the software ourselves, but in reality there wasn’t a lot that could be used to make these efficiencies happen.

Take food waste as an example. Supermarkets waste 35% of their products. When we first saw that number as data people, we thought it was appalling. Why is that number so high? At Farmstead, the goal was to have [food waste in] single digits while aggressively adding more customers.

One of the challenges of Farmstead is that we also are not like a supermarket, in that we don’t just have a three- to five-mile radius around our store. Our locations have a 50-mile radius. Approximately 10 to 12 stores’ worth of demand can potentially be connected to one of our locations. As a result, while the number of customers we have is increasing, we still have to keep the food waste low.

Supermarkets typically have one person in charge of one or two aisles of product, and most buyers are making gut calls on produce and perishables projections, saying they need to buy an extra case of carrots because it was moving fast last week. But that’s a very inefficient way of buying. In reality, software should be doing that, so we buy all our products using software. There are no purchase orders that are generated by people, it’s all generated by code.

We reached 20% food waste after implementing the software, but still didn’t achieve our sub-8% goal. We realized that using our software alone was not enough. Then we turned on our machine learning layer to take into account all the historical sales data, all the seasonality for any particular item. By that, I mean buying more croissants for Friday, Saturday or Sunday, and buying more heavy cream during Thanksgiving time. The machine learning makes a prediction for every single item, for every single location, saying buy ‘this much’ and not ‘that much’. With that model in play, our food waste is now well under 10%.

We also built our inventory control from scratch. Most inventory control systems don’t support perishable sell-by dates that well. We did the same thing for picking-and-packing, where we used off-the-shelf scanners to create an efficient system that we control 100%. This allows us to pack a $150 order in five minutes.

We built software for our drivers, so they can go on these long delivery routes. They show up at our location, they grab the orders to put them in their car and the software tells them to drop the items off at house A, house B, house C in this specific order. A lot of things had to go right for all this to click into place, but the heart of it is our software that we’ve spent a lot of time developing.

RTP: Where do you feel machine learning and AI solutions fit into overall grocery strategies, and how should companies use this technology to their advantage?

Elankumaran: Machine learning is very good at predicting, and enterprises — not just grocers — are bad at predicting. A lot of the reasons that costs overrun are that predictions are really off. We have doubled down on machine learning to predict inventory, which is the number one cost for us. Very soon we are going to predict:

- How many drivers will we need?

- What’s the probability of those drivers going to those locations?

- How many people do we need picking and packing these orders on any given day?

Grocers need to understand that the assumption that shoppers will always come to your location is changing, and in order for someone to support that change, it requires a certain level of sophistication around what needs to happen in real time. Any particular location you start has to have an increasing number of customers connected to it.

Machine learning for prediction is something that is very underutilized in grocery, and in general.

RTP: How does Farmstead go about understanding (and catering to) evolving consumer preferences, especially given your locally-sourced product offering?

Elankumaran: We’ve been collecting customer feedback for a very long time — since the day we started. The majority of items on Farmstead are added because customers tell us that they want them. We also have usage patterns. For example, someone is searching and they type in “cranberry sauce” and if we don’t have that, we can look at our reports to see that consumers may want cranberry sauce, and we should probably add it.

The biggest way that we add items is that people tell us ‘It would be nice if we carried this brand.’ For a while, there was a lot of demand for raw milk, and it wasn’t something we planned on adding, but we kept getting more people who wanted it. And they kept searching for ‘raw milk’ on Farmstead. We said, ‘You know what, let’s try it,’ and now raw milk has been a top-10 seller on Farmstead for a long time.

The worst thing we can do is have a lot of inventory that’s not selling. My nightmare scenario is having all the product that a supermarket has that is just sitting there, and it’s just one or two customers buying something every week. That’s not what we’re about. We’re trying to bring in the products that will move and will also have a higher probability of being part of your weekly basket.