Williams-Sonoma thought they had a hit on their hands. The retailer had introduced a home “bread bakery” machine into their stores for $275. But consumers weren’t interested. They chose the nearby French press or mini grill instead.

Williams-Sonoma thought they had a hit on their hands. The retailer had introduced a home “bread bakery” machine into their stores for $275. But consumers weren’t interested. They chose the nearby French press or mini grill instead.

Instead of yanking the bread maker, Williams-Sonoma changed how it was presented. They added a larger model of the bread maker priced about 50% higher. Suddenly, the $275 version began to fly off the shelves. Given two breadmaker models to choose from, people saw the smaller one for less money as the better deal, and they pounced.

This is a classic example of the “decoy effect,” a marketing principle first demonstrated by Duke University researchers in 1982. They found that a product will be perceived as more valuable if the buyer can compare it to a less desirable model on the shelf or a web page. It’s just one of endless factors that can influence whether a shopper will jump at an offer.

“Most people don’t know what they want unless they see it in context,” says Dan Ariely, expert on behavioral economics, who tells this story in his groundbreaking book Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions. “Don’t underestimate the power of presentation.”

Retailers spend the vast majority of their time thinking about what an offer or promotion should be: What is the discount, what are terms and conditions, etc. But behavioral science shows that how an offer is presented can be just as powerful — often even more powerful — in driving a purchase decision.

My team spent years scouring the latest academic findings from behavioral economics and cognitive psychology to learn how to more effectively deploy incentives. We then built a software platform to give retailers an easy way to harness those insights to make better offers.

Through thousands of campaigns, we’ve discovered some pretty exciting lessons. Here are five best practices to reliably increase redemptions by changing how an offer is presented.

Best Practice #1: Make It Fun

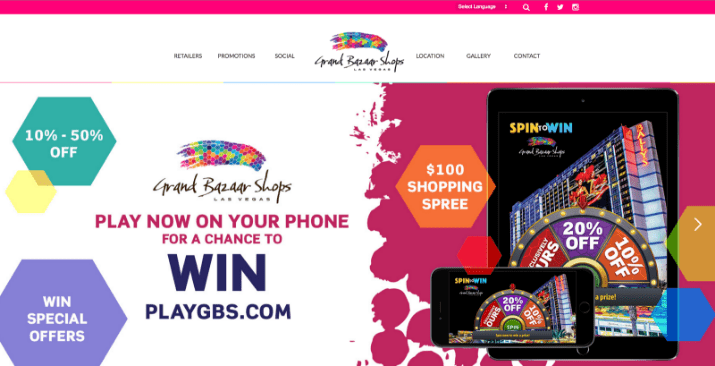

To make your offers memorable, they need to be fun. And the easiest way to make them fun is to present them in the form of a game.

Imagine you’re at checkout at your favorite retailer. Instead of shoving a coupon in your hands, the sales associate says, “While you pay, would you like to play?” As she rings up your purchases, you play a fun wheel spin game on a tablet and win, say, a discount on your next purchase. You enter your email address or cell number and the “prize” — which is often the same coupon you would have received without the game — is sent to your phone.

Even if the coupon and the prize have an identical monetary value, most consumers will feel like the prize they won or earned is more valuable than just getting a coupon at the bottom of a receipt. As a result, the gamified reward will be redeemed more frequently than the traditional coupon.

“When we play, we are engaged in the purest expression of our humanity, the truest expression of our individuality,” says psychiatrist Stuart Brown. “Is it any wonder that often the times we feel most alive, those that make up our best memories, are moments of play?”

Best Practice #2: The Exact Words You Use Have A Huge Impact

The precise words and scripting you use to present an offer matter. A lot.

Imagine there’s a clothing store that needs to sell more belts.

Now say you’re buying a pair of pants at this store. Typically the sales associate might try to upsell you by saying something like, “Would you also like to buy a $15 belt with your $60 pants?” That will work for some people, but not most of us.

But now imagine a different sales associate says, “These $75 pants come with a thank you gift: Your choice of one of these belts. You can take any of these, or you can give back the belt to reduce the price a little.”

Instead of deciding to make an additional purchase, you’re now asked to actively give back a gift. This enterprising sales associate will generally sell a lot more belts than his counterpart.

“When done properly, gifts work like nothing else. A gift gladly accepted changes everything,” says marketing expert and author Seth Godin. “We like getting gifts, we like being close to people who have given us a gift and might do it again.”

This is just one of countless ways that psychology can be used when scripting an incentive to recast how an offer is made.

And of course, it’s not just the words you use to present an offer, but how you say them. No matter how interesting the deal is, if the sales associate who’s actually presenting the offer doesn’t exude excitement, energy and professionalism, it’s not going to work.

Best Practice #3: The Power Of Choice

One of our retail clients offers a fascinating example of the power of choice.

They ran a promotion where they gave their most loyal customers a $100 credit toward certain products. But then they offered those same customers a chance to swap that $100 credit for a $50 credit on a different product.

The results were startling: more than one third (34.9%) of the customers swapped the higher value prize for the lower value prize on a different product. The customers were happier, while the retailer cut promotional costs significantly and generated invaluable insights about the preferences of their best customers.

Best Practice #4: Test, Test…Then Test Again

Online retailers are constantly testing how to best present their offers.

This process, called optimization, involves creating a series of so-called A/B tests where you tweak one aspect of the presentation — the call to action, the product images used to showcase inventory, etc. — and then watch how it impacts conversion.

My favorite example of this is the color of the “Buy” button. Internet retailers are forever debating what color drives the highest conversions rates. Amazon, a famous optimizer, is said to have tested hundreds of different colors before settling on BOB, the Big Orange Button. The BOB camp argues that orange is the most visible color right after red, but it doesn’t raise all the negative emotions.

But customers change, and Amazon continues to test and evolve its button color, along with every other aspect of its presentation. Conditions and consumer preferences are constantly evolving, which means you have to continually be optimizing to keep up.

Best Practice #5: Personalize How You Offer, Not Just What You Offer

Now that brands and businesses have access to reams of personalized customer data, and can track and even predict customer behavior and preferences, they can create offers tailored to the individual’s wants and needs.

No surprise here: most retailers just focus on what offer to make. Yet there are a whole host of more subtle variables that allow for deeper personalization and effectiveness. For example:

-

Customer A says she prefers to get an offer via a certain channel, like email…but in reality the data shows she is far more likely to redeem an offer that she gets via a different channel, like text or social media.

-

We might learn that Customer B is twice as likely to actually use an offer presented after he has been shopping for a few minutes versus an offer presented at the start of the shopping experience.

-

Customer C might have dramatically different shopping habits at 10 a.m. versus 10 p.m. — so it may make sense to present offers to her that can only be used during the more profitable time of day.

In short, changing how something is presented can fundamentally change the shopping experience and deliver far higher revenues. There’s no debate here. Reimagining how you craft your offers can quickly become a dramatic competitive advantage.

Aron Ezra is the CEO of OfferCraft, a fast-growing software company that helps organizations present marketing offers and employee incentives in the most effective way possible. He was previously the CEO of MacroView Labs, a mobile software company that served the hospitality, retail, travel, event and entertainment markets. Ezra has worked in senior roles at Bally Technologies, PR agency Hill & Knowlton, and research and consulting firm The Advisory Board Company. He has given more than 800 presentations on technology and marketing issues at conferences worldwide. He advises several tech startups and accelerators and graduated from Princeton University.